fire, blood, and heavenly immanence

early British saints pt.2: an overview of the historical context and the medieval worldview

Today’s post is a follow-up to my last post, which introduced a new series on the lives of early saints of the British Isles that I will be releasing over the next year. In it I will outline a brief overview of the period from a historical perspective, and offer a few notes on the worldview of early medieval Christians.

Before we begin, I would like to reiterate that this series is not intended as an exercise in early medieval history, I studied history for my undergraduate degree, but I am not a historian, let alone an expert on the early medieval period. There are many things in the stories of these saints lives that will seem impossible to a modern reader, and that cannot be “proved” by modern historical research. I am not going to attempt to prove them. To quote Orthodox theologian Eugenia Scarvelis Constantinou, writing about the ancient Tradition of the Church that the Theotokos dwelt in the Holy of Holies, “Trying to historically or rationally justify it is pointless, and it is ultimately of no importance whether it is historically defensible. The question for us always is: What spiritual lesson is the Church presenting for us?”1 The lives of these saints contain deep spiritual value beyond their literal historical meaning. However, historical context is important and illuminating, so I thought it would be helpful to give a very brief overview of the period to help readers contextualise the world in which these saints lived. This is necessarily a simplified summary, and should be understood as such. There are vigorous debates amongst historians about almost everything we know about this period. I have relied heavily on Early Medieval Britain: c. 500 - 1000 by Rory Naismith, which I recommend for anyone who wishes to gain a more comprehensive understanding of this period.

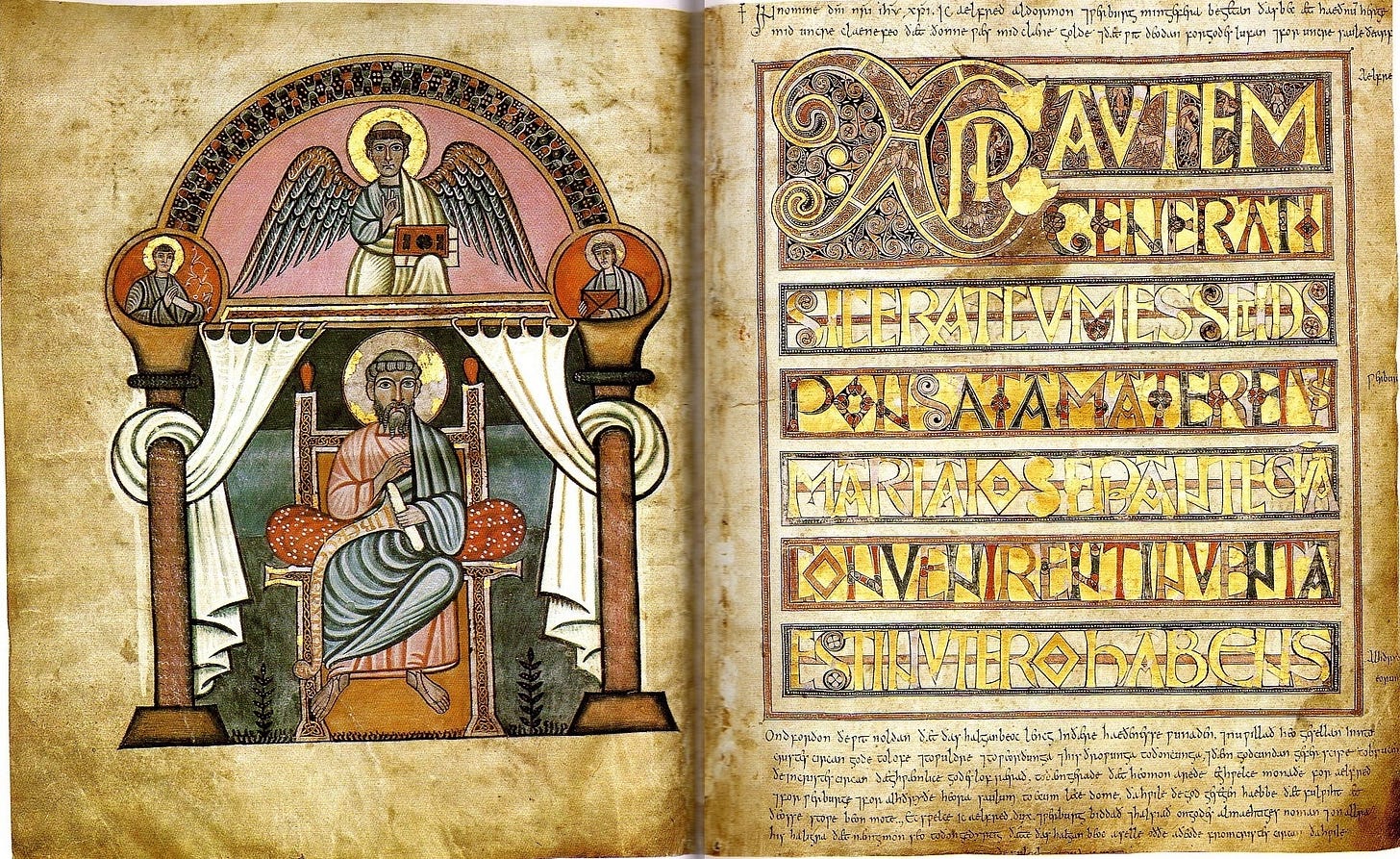

Early medieval Britain is a relatively obscure and little known period of history. The six and a half centuries from the end of Roman rule in c. 410 to the Norman Conquest of 1066 used to be disparagingly referred to as the Dark Ages, because of the lack of contemporary written sources for the period and the perceived lack of scientific and cultural advancement. It was a period of change and upheaval, accompanied by significant political and religious transformation.

The End of Roman Britain: 383-449

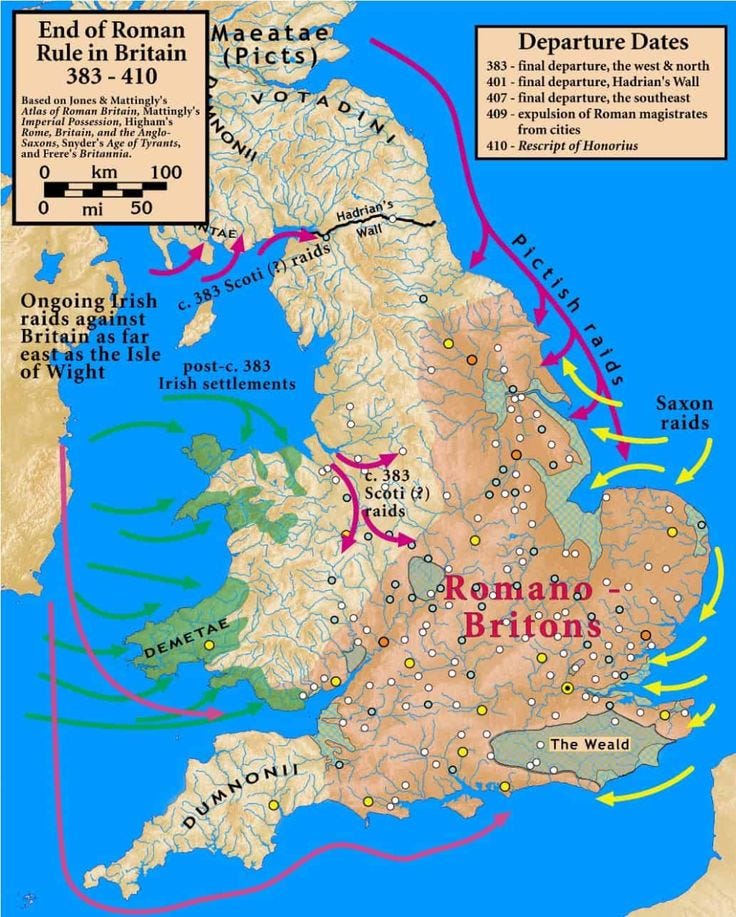

In 400 AD, large parts of Britain were part of a Roman Empire that, although increasingly beleaguered, still stretched from the Irish Sea to the river Euphrates. During the relatively stable 350 years of Roman rule, a network of roads, military bases, and towns were built by Roman legions, initially to facilitate the movement and supply of Roman troops.2 Trade and industry flourished, and Roman culture, including the Latin language, became widespread, at least amongst the social elites. Christian legionaries and merchants introduced Christianity,3 which seems to have been well established in Romano-British4 culture by the end of the fourth century. Roman rule extended far into the northern parts of what is now England and Scotland, with the Antonine Wall representing the northernmost limit of Roman control. Roman influence was not exerted uniformly, and Naismith notes that “Western parts of the Roman province such as what is now Cornwall and central and north Wales were less integrated into the cultural and economic networks of the empire…the comparative development of Roman Britain came at the cost of a more intensely exploited rural population, who had to satisfy the demands of landlords and imperial taxes.”5

Britain detached itself politically from the empire during the fifth century, and entered a century of upheaval. It is commonly thought that the Roman empire withdrew its legions and left Britain, but this is not entirely accurate. During the fourth century the soldiers stationed in Britain nominated various usurpers who challenged the central authorities, with three usurpers appearing in quick succession in 406. The last of these, Constantine III, took many of the remaining British legions to campaign in Gaul, where he was eventually defeated and killed. By this point the Britons had also turned against Constantine and decided to rely on their own resources. Naismith writes that “Roman withdrawal from Britain, then, in the form of Constantine and other rebels denuding the province of armed forces, therefore needs to be kept distinct from the end of central Roman rule in Britain: the latter seems to have been a local action, and was not a conscious decision by the imperial administration to abandon one of its provinces.”6

The early part of the fifth century in Britain saw the disappearance of a standing army, the collapse of provincial bureaucracy, and cultural and economic decline. Post-Roman Britain remained predominantly Christian, and seems to have retained many Roman practices in law, learning and the structure of society, albeit in less centralised ways. It would not remain so for long, and the following century saw the arrival of Germanic peoples who became known as the Anglo-Saxons.

The Anglo-Saxon Settlement: 449-597

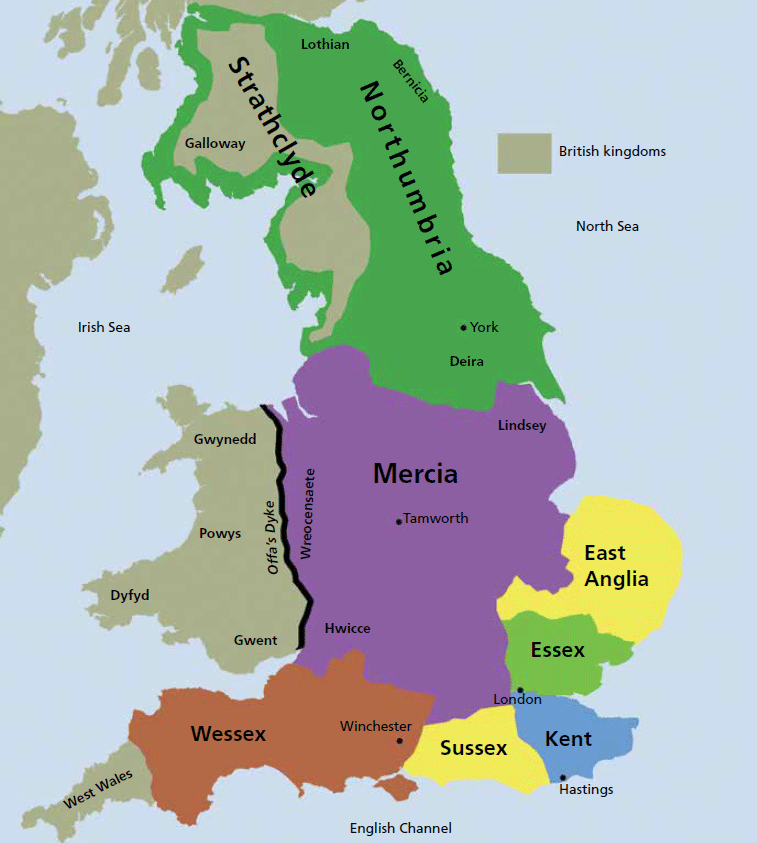

The first enemies of the newly-independent Britons were Irish raiders from the west and Picts from the north. However, they were not the last. The English origin story is famously told by Bede in his The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, which was completed in 731. Bede records that in 449 warlike tribes he calls the Angles, Saxons and Jutes arrived by sea from what is now northern Germany and Denmark, on the invitation of British King Vortigern, who intended for them to repel the Irish and Picts. According to Bede, they soon turned on the Britons, and “scattered and destroyed the native peoples”.7 The pagan newcomers established kingdoms across the southern and eastern parts of Britain, pushing the remaining Christian Romano-British population to more remote regions further west and north, Cornwall, Wales, and Scotland. Bede drew heavily on an earlier source from the late fifth or sixth century, On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain. This was written by a British deacon named Gildas, who regarded the coming of the Saxons as a divine punishment on his countrymen for their sin. Both Bede and Gildas tell a story of violent invasion by the Saxon peoples, who established their kingdoms using fire and blood. Modern historians have challenged this depiction, however there is no doubt that the material culture of Britain changed dramatically during the fifth century, suggesting that what D. N. Dumville calls ‘cultural genocide’8 occurred, even if mass slaughter was limited. Regardless of how they arrived, by 500 the Germanic speaking newcomers had settled deep into Britain and established kingdoms.

Both Bede and Gildas record how the Britons successfully counter-attacked under Ambrosius Aurelianus, ‘the last of the Romans’. It’s during this early period that the figure of Arthur – possibly completely legendary – emerges. A record made three centuries later credits him with 12 battles, from Scotland to the south coast. Only the last, in about 500, is confirmed in earlier sources – but it makes no mention of Arthur. This British victory halted the Saxon advance for half a century.

In independent kingdoms across the north and west, the British also resisted the repeated onslaughts of the peoples who were later called ‘English’. But by the 650s, almost all the lowlands were under English control.

Consolidation and Conversion: 597-800

Christianity in the eastern parts of Britain was almost wiped out, although it survived in the western British kingdoms.9 The church in these regions, sometimes referred to as Celtic Christianity, developed in isolation from the rest of Western Christendom, under the influence of missionaries from Ireland.10 The remaining Britons seem to have made no attempts to evangelise the Saxons, which is perhaps understandable. Bede recordes how the pagan Saxon kingdoms were eventually converted to Christianity after Pope Gregory the Great sent a missionary team headed by St Augustine (not to be confused with St Augustine of Hippo) to evangelise the Anglo-Saxons in 597. King Æthelberht converted to Christianity and gave St Augustine permission to preach freely and land to establish a monastery. St Augustine became the first bishop of Canterbury, and founded the Anglo-Saxon church in the south of England. Bede, who was himself Northumbrian, also records how Irish missionaries played an important role in the conversion of the northern Saxons, especially in Northumbria. St Aidan of Lindisfarne, who died in 651, established a monastery on the island of Lindisfarne, served as its first bishop, and travelled tirelessly across Northumbria spreading the Gospel to men, women and children from all classes of society, from nobility to slaves.11

The process and speed of conversion varied by region, and kingdoms often reverted to paganism after their first Christian king, but by the beginning of the seventh century the Anglo-Saxons had well established kingdoms and a vigorous Christian culture. The seventh and eighth centuries saw an era of consolidation, with the kingdoms of Northumbria, Mercia and Wessex establishing a three-way balance that lasted until the Viking invasions led to the carving up of the kingdom of Northumbria in the ninth century.

The creation of a unified Christian culture was not instant. Eleanor Parker notes in Winters in the World that in the early medieval period, “religious conversion was frequently a collective rather than an individual process, and it marked a profound cultural shift”12. A key feature of this was the introduction of a shared liturgical calendar, observed by the whole of society. The liturgical calendar that developed during the six centuries of the Anglo-Saxon period was “among the most enduring aspects of English life…through more than a thousand years of religious, political and social upheaval the basic pattern of the festival year remained a stable part of life.”13 As previously noted, the Celtic church that had developed in isolation from Roman Christendom held to several distinctive practices, notably a different way of calculating the date of Easter. St Augustine of Canterbury failed to persuade the Celtic bishops to reconcile with their Anglo-Saxon neighbours, or to give up their distinctive practices. The first meeting near Gloucester was unsuccessful, and the second, the Synod of Chester, was disastrous. St Augustine, failing to heed the advice of Pope Gregory against pride, deeply offended the Celtic bishops when he did not do them the common brotherly courtesy of rising to greet them on their arrival, instead electing to remain seated in the manner of a Roman magistrate, signifying his superiority over them. Differences in practice between the Roman and Celtic branches of the British church persisted, and it wasn’t until the Synod of Whitby in 664 that the ongoing controversy between Roman and Celtic Christianity over how the date of Easter ought to be calculated was settled. Christianity flourished in the seventh and eighth centuries, energising early medieval British societies from top to bottom. These centuries were also the golden age of monastic foundation, with hundreds of monasteries set up and a major transfer of land and wealth from the aristocracy to the religious houses. An interesting feature of early Anglo-Saxon monasticism is the appearance of ‘double monasteries’ that housed both men and women, normally with strict separation of the sexes. These double monasteries, which included famous institutions like Whitby and Barking, were often headed by a female abbess, usually a woman drawn from an aristocratic or even royal background. Monasteries were integral to the cultural and spiritual life of wider society, and although some sought solitude as hermits, many monks and nuns were deeply involved with the world around them, providing an exemplary model for the spiritual life within society rather than a complete withdrawal. Many of the saints that we will encounter were monastics, and even secular historians note that holy men and women are “one of the most conspicuous legacies of the early Middle Ages.”14

Crisis and Consolidation: 800-1000

The century and a half leading up to the first millennium saw Britain face severe challenges, notably in the form of waves of viking invaders, who conducted raids and established kingdoms across Britain. This crisis led to the consolidation of power into the kingdoms of Alba and England, nascent forerunners of Scotland and England respectively. Trade between Britain and Scandinavia had been ongoing for generations before the raids began, but where “once there had been commerce and balanced exchange, now parties of vikings took what they wanted by force”15. In 851 the first viking army spent the winter on the Isle of Thanet in Kent, and in 865 a large force arrived in East Anglia and campaigned across Britain, Ireland and mainland Europe for more than a decade. This ‘great army’, as it was called in The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, was very successful: East Anglia was conquered in 865, Northumbria and Mercia in 867 and 874 respectively. Initially the vikings do not seem to have settled in areas they conquered, instead appointing compliant local rulers, but by the later 870s and 880s enough of the ‘great army’ had settled down to give rise to what became known as the Danelaw. In the south, the remaining kingdom of Wessex faced enormous pressure during the 870s, with Alfred the Great ascending to the throne in 871 in the middle of a military crisis. Alfred successfully defended his kingdom against the viking invaders, decisively defeating a viking army at Edington in 878. His reign also saw the consolidation of the remaining Saxon kingdoms into a new “kingdom of the Anglo-Saxons”, as the remnant of the kingdom of Mercia united with Wessex under Alfred’s leadership. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes Alfred as ‘king over the whole English people save for the part that was under Danish rule’ by the time of his death, and Alfred’s successors would further establish the boundaries of Anglo-Saxon rule over the next fifty years, finally retaking York from the vikings in 954. Viking raids resumed in the 980s, developing into full-scale invasions which eventually overwhelmed the disastrous King Æthelred ‘Unready’ (r.978–1016). The Danish leader Cnut (r.1016–35), later also King of Denmark and Norway, was popularly recognised as Æthelred’s successor and made England part of a Scandinavian empire. The old West Saxon (Wessex) dynasty was revived with the accession of Edward the Confessor in 1042. But when he died without heirs in 1066, Harold Godwinson seized the throne. England was immediately threatened both by Cnut’s heir, Harald Hardrada of Norway, and Edward’s choice of successor, Duke William of Normandy. Hardrada invaded first and was beaten at Stamford Bridge in Yorkshire, on 25 September 1066. Harold marched his weakened army south to face William at the Battle of Hastings, the outcome of which would open up an entirely new chapter in the story of England.

I hope that this very potted and abridged version of the Anglo-Saxon period was interesting and gives you an insight into the world in which the early British saints lived. These men and women lived in uncertain and tumultuous times. There were periods of peace and prosperity, but many also lived through times of severe crisis and upheaval.

an enchanted world: inside the medieval mind

I want to finish by touching briefly on one aspect of the worldview of early medieval people. I believe this to be important, because it contrasts so sharply with the dominant worldview of most modern people, and I don’t think that we can hope to understand the lives of these saints if we don’t grasp this idea. For this section I have drawn heavily on two books, Journey to Reality by Zachary Porcu, and The Age of Paradise by John Strickland, both of which I read recently and highly recommend.

Modern people typically view the physical and spiritual worlds as separate realities, and “tend to think of the supernatural as operating on some different level or dimension and therefore as being mostly irrelevant to the day-to-day operations of the natural world.” This was not the case in either the ancient world or the early medieval period. Ancient people saw the physical and spiritual as “fundamentally interrelated” and saw the main difference between the two as one of visibility. They saw the physical world as visible and the spiritual world as invisible, but “they never thought of them as separate”.16 Porcu explains that viewing the spiritual and physical as fundamentally inseparable has important implications, one of which is the idea of intrinsic meaning. Modern people consider the physical world to be “simply what it is…a tree is just a tree, a triangle is just a triangle, and so on…any meaning they have is something we make up ourselves and impose on them.” He contrasts this with the sacramental worldview, in which the whole universe and everything in it has intrinsic meaning. He gives the example of the shape of the cross, and explains that

“If you see the spiritual and physical as separate, the shape…is just a couple of lines. It might have personal significance for one person but mean something totally different (or nothing) to someone else. It has no intrinsic meaning. But in the sacramental view of the world, the shape of the cross has intrinsic meaning with reference to the Christian story. If the Cross is truly the weapon by which Christ defeated death and evil, then the shape of the cross has more than personal significance - it has cosmic significance. The shape itself has power, regardless of whether the person who drew it knows that or not. That’s why, for example, in certain traditional beliefs, a vampire is physically harmed by the sign of the cross, because a vampire has its power from the devil.”17

Another way of putting this is to say that the world is enchanted. The modern world is disenchanted, and reality is widely believed to be “just” what we can see and feel, with no inherent meaning. The enchanted view is that “because of the connection between the physical and the spiritual, everything in the physical world has some intrinsic meaning, whether or not we’re aware of it”18

In the early medieval period, both pagans and Christians agreed that the world they inhabited was one full of enchantment. However, early Christians also believed a “radical set of new ideas that no one had ever imagined until that point…those ideas would transform the entire pagan world down to its very foundations.” Most pagans believed in some kind of ultimate reality that existed beyond the pantheon of divine and semi divine beings who were worshipped as gods, but they “were often skeptical about their ability to interact with it or understand it.”19 They also largely viewed the physical body as inherently corruptible and something that needed to be transcended in order to escape human nature. The Christian doctrine of the Incarnation, which taught that God actually became human in the person of Jesus Christ, who was fully man and fully God, showed that “God did not remain aloof from His creation but became incarnate, filling the world with heavenly immanence.”20 This heavenly immanence could be experienced by believers through the sacraments, especially the Eucharist. By participating in the sacramental life of the Church, Christians were able to “participate in the very life of God”.21 Strickland writes that,

“By the eighth century, then, the culture of Christian romanitas - whether in the East or the West - had become thoroughly imbued with the sacramental character of worship. God’s presence was very nearly everywhere felt…An experience of the divine had, indeed, been characteristic of pagan romanitas before Pentecost. The temples scattered throughout the empire’s towns and cities, the miraculous portents, the seasonal festivals - all of these manifested divine activity on earth…Unlike paganism, however, traditional Christianity claimed that there was one true God, and that His only-begotten Son had come to Earth in the Incarnation. It claimed that through the sacramental life of His Church, that very God continued to fill the world He had created with His divine presence.”22

The principle of heavenly immanence was spiritually transformative. The way time was measured was transformed, with “daily, weekly and annual cycles of time reoriented to the liturgical calendar.” In the Christian liturgical year early medieval men and women celebrated and reenacted the story of Christ through the seasons, rituals and traditions of the church. Space itself became sanctified, and “Christendom became a civilization of pilgrimage” as believers “sought out places that manifested the material presence of divine grace. Where saints’ bodies reposed and the sacramental life of the Church was conducted, they believed, God dwelt on earth among men.”23 The remains of saints were treasured because the Incarnation had “sanctified not only the human spirit, but the human body as well”.24 Pilgrimage “introduced the believer not only to the possibility proclaimed by the Gospel of personal transformation, but to that of the spiritual renewal of society itself.”25

This is the world that the men and women who we will meet over the coming months inhabited. It was a world that was enchanted, in which the spiritual was every bit as real as the physical. Most importantly, it was a world in which the Church and culture of Christendom shared one principal goal: “to bring man into an experience of the kingdom of heaven while living on the earth.”26

Thank you so much for reading, I look forward to hearing your thoughts or comments. Next week we will encounter our first saint, St Winifred of Holywell. My husband and I got married in the remains of the Abbey where St Winifred’s relics were originally venerated, so I am really looking forward to sharing her story with you.

Eugenia Scarvelis Constantinou, Thinking Orthodox: Understanding and Acquiring the Orthodox Christian Mind (Ancient Faith Publishing, 2020), p.230

Towns established in the Roman period include some of the most important in Britain, including Lincoln, London, and York, as well as Chester and Exeter.

In legend, the first Christian community was established at Glastonbury by Joseph of Arimathea – uncle to Jesus Christ and a wealthy tin merchant – who returned some years after the crucifixion (maybe CE 63) with a company of twelve holy men. Supposedly, Joseph of Arimathea also brought the cup from the Last Supper with him along with two small cruets containing the blood and sweat of the Christ on the cross. According to Devonian and Cornish folklore, Jesus Christ himself travelled to the West Country with his uncle Joseph during his youth. This is famously referred to in the poem Jerusalem by William Blake: “And did those feet in ancient time walk upon England's mountains green”.

Rory Naismith notes that “Although it is common to refer to the inhabitants of Britain in the time of the Roman Empire as Romano-British, after the early third century all free men in the empire were citizens (and all free women had the same rights as Roman women); the Britons, therefore were just as Roman as the inhabitants of Rome itself.” Early Medieval Britain, (Cambridge University Press, 2021), p.20

Naismith, Early Medieval Britain, p.150

Naismith, Early Medieval Britain, p.152

Bede, The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, chapter 16

D. N. Dumville, ‘Origins of the Kingdom of the English’, in R. Naismith and D. Woodman (eds.), Writing, Kingship and Power in Anglo-Saxon England (Cambridge University Press, 2017), p.75

Bede did believe that the cult of St Alban survived and records that it was practised continually from the time of the Romans until his own day. However, the organised church seems to have been almost completely wiped out in areas under Anglo-Saxon control.

There is debate amongst historians about the term “Celtic Christianity”. Most modern scholars reject the idea of a "Celtic Church" because there's little evidence to support it. However, there were distinct Irish and British church traditions with their own practices, including a different system for the dating of Easter, a different style of monastic tonsure, and an ecclesiastical structure that was primarily monastic in nature.

Bede also wrote a detailed life of St Aidan, which is the primary source for modern biographies of the saint.

Eleanor Parker, Winters in the World: A Journey Through the Anglo-Saxon Year (Reaktion Books, 2022), p.19

Parker, Winters in the World, p.10

Naismith, Early Medieval Britain, p.319

Naismith, Early Medieval Britain, p.223

Zachary Porcu, Journey to Reality: Sacramental Life in a Secular Age (Ancient Faith Publishing, 2024), p.48-49

Porcu, Journey to Reality, p.49-50

Porcu, Journey to Reality, p.50-51

Porcu, Journey to Reality, p.102

John Strickland, The Age of Paradise: Christendom from Pentecost to the First Millenium (Ancient Faith Publishing, 2019), p.47

Strickland, The Age of Paradise, p.43

Strickland, The Age of Paradise, p.158-159

Strickland, The Age of Paradise, p.165

Strickland, The Age of Paradise, p.164

Strickland, The Age of Paradise, p.166

Strickland, The Age of Paradise, p.55

Absolutely lovely - thank you for taking the time to tease out this complicated web of history, when so often, we can only briefly gloss over it.

Your quote from Eleanor - about collective rather than individual conversion - was something that came up at our book club gathering!

WOW! For me, this is an incredible article. I will have to re-read it a few times to digest it. Thank you.