Welcome back to the next installment of my series on Saints of Early Medieval Britain. You can read the introduction to the series here, an historical overview of British history c.400-1000 here, and the first essay on St Winifred here.

I know it has been quite a long time since I published the piece on St Winifred, so I want to thank you all for your patience. The last month has been a very busy one for me with work and family commitments, so I have not had as much time as I had hoped to put towards writing. For today’s essay I have chosen to focus on St. Edburga of Thanet, whose feast day is celebrated on December 12th (or December 13th? I’ve seen both dates listed online). A woman of royal birth, St. Edburga chose to forgo marriage and motherhood and instead embraced the monastic life, becoming abbess of a prominent double monastery. Enjoy!

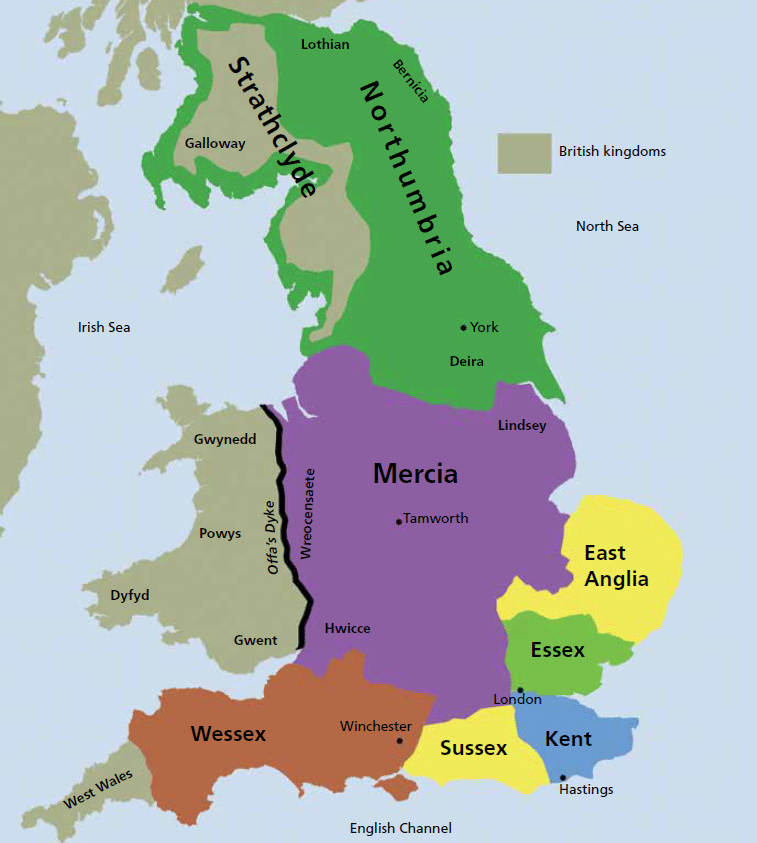

Eighth century Britain was a patchwork of competing kingdoms. After the collapse of late Roman Britain and the chaotic and often violent settlement of various Anglo-Saxon peoples in the fifth and sixth centuries, the period from around 600-800 was relatively peaceful, marked by political consolidation and the formation of larger and more stable kingdoms, pictured below. As I noted in my historical overview of the period,

Anglo-Saxon society was a decentralised and predominantly rural one. Even in larger kingdoms such as Mercia, the power of the monarch was far from absolute, and there were other, often overlapping, power structures that existed alongside and sometimes in tension with, royal claims of authority. These included the claims of local nobles and lords, ecclesiastical authorities including bishops and monastic leaders, mayors and sheriffs if you lived near a town, and of course, networks of wider family, which formed the basic unit of society.

Interestingly, Rory Naismith comments that whilst the notion of lordship “became dominant and pervasive outside the aristocracy, especially in the tenth century…one of its principal enemies was over-mighty kin-groups. Anglo-Saxon law can sometimes look like a drawn-out fight against such kindreds, in favour of king, lord and individual responsibility.”1

‘Double Monasteries’: A Unique Feature of Anglo-Saxon Monasticism

A notable feature of this period is the flourishing of monastic communities across Britain, with many historians regarding this as a golden age of British monasticism.

Double monasteries were founded from the 630s onwards and flourished until the Viking attacks of the ninth century, and tended to draw their leaders from aristocratic or royal women. Rory Naismith comments that “this elite connection is key to the popularity of double monasteries: they provided a protected, respected and relatively comfortable alternative to marriage, which was attractive to noble and royal women who either never married or were left without a husband - both of which positions were vulnerable. At the same time, abbesses maintained a role in public life”.2

One of these double monasteries was the monastery at Minster-in-Thanet, Kent. The island of Thanet was where St. Augustine had first landed on his mission to convert the English in 597, and a monastery had been established there by St. Ermenburgh, a widowed queen and part of the kentish royal family. According to tradition, King Ecgbert (who was St. Ermenburgh’s cousin) gifted St. Ermenburgh the land to found her monastery after one of his advisors murdered St. Ermenburgh’s two young brothers. Learning about the murder, St. Ermenburgh demanded a wergild, that is, an atonement for her relatives’ killing, which was the custom of the time. Rather than money or riches, she asked King Ecgbert to gift her land on the Isle of Thanet on which she could found a monastery. King Ecgbert was apparently full of grief and repentance and agreed to her request. Legend has it that Ermenburgh requested that the land that her tame hind walked around would be given to her to found a monastery. The hind walked around a vast area in Thanet and a community of seventy nuns was subsequently founded there, with the widowed Ermenburgh becoming the first Abbess. In 694 she resigned her abbacy in favour of her daughter, St. Mildred, who became the friend and spiritual mentor of St. Edburga.

St. Edburga of Thanet (died 759)

St. Edburga was the only child of King Centwine of Wessex. Her exact date of birth is unknown, although it must have been prior to her father’s death in 686. According to The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Centwine became King of Wessex in c.676 and ruled until his death in 686. Bede refers to a period of instability and fragmentation following the death of King Cenwalh in c.645, claiming that Wessex was ruled by a number of sub-kings. It is possible that Centwine was one of these sub-kings, or that under his rule Wessex was reunited into one kingdom. At some point after her father’s death, Edburga left Wessex and became a disciple of St. Mildred, who was Abbess of Minster-in-Thanet Abbey in Kent, another Anglo-Saxon kingdom. Edburga took her vows and entered the Abbey at Minster in 716, eventually succeeding St. Mildred as Abbess in 733 after the latter’s death. A woman of great ability and intellect, she secured several Royal charters for her monastery. She was also a friend and correspondent of St. Boniface, the great missionary to the Germans, and he wrote her several interesting letters, which span a period of thirty years. The correspondence is unfortunately one-sided, as the letters which Edburga wrote to Boniface in reply have not been preserved. It seems that Edburga and Boniface originally met in Rome when Edburga was there on a pilgrimage with her mother, presumably prior to her joining Minster Abbey in 716.3 The first letter, which dates from 716, contains a long description of some visions recited by a monk who died and came back to life.4 Another contains a request for Edburga, who had a reputation as a skilled calligrapher, to “copy in gold the Epistles of my lord, Saint Peter, that the Holy Scriptures may be honoured and reverenced when the preacher holds them before the eyes of the heathen”. Another contains his thanks for books that she has sent to him:

To his dear sister, the abbess Edburga, long united to him by spiritual ties, Boniface, a servant of the servants of God, sends greetings in Christ.

May the Eternal Rewarder of all good works give heavenly joy among the choirs of angels to my dearest sister, who has sent light and comfort to an exile in Germany by sending him gifts of spiritual books. No one can survive in these gloomy places serving the German people unless the Word of God shines like a lamp about his path.

I beg of your love to pray for me, because as a punishment for my sins I am being tossed around by the storms of this world. May God remember me, that I may speak out boldly, so that the Word of God may run with victory, and the gospel of Christ be glorified among heathen people.

- Letter of Boniface to Edburga, c735

In time, St. Edburga built a new church for her monastery and removed into it the body of her predecessor, St. Mildred. St. Edburga died at Minster on 13th December AD 759 and was buried alongside St Mildred, although her remains seem to subsequently been translated to the parish church of Lyminge.5

According to tradition, St. Edburga also trained St. Leoba, a notable saint in her own right, who joined another prominent double monastery, Wimborne Abbey in Dorset, before leaving the British Isles to join St. Boniface in his missionary efforts.

In many ways, St. Edburga led a rather unremarkable life, and unlike St. Winifred, there are no dramatic or exciting legends attached to her. She spent most of her life within the confines of Minster Abbey, where she lived a life of quiet devotion.

St. Edburga might have lived a quiet life at Minster, but she was intimately connected with the mission to convert the Germans, both through her friendship with St. Boniface, and her role as mentor and spiritual mother to the younger and more well known St. Leoba, who would join St. Boniface in his work. Her role was a supporting one, out of the spotlight, quietly assisting St. Boniface in the ways that she could, through practical assistance and prayer.

What, then, can we learn from her life? The documentary evidence is scant, so I am aware that I must be careful not to draw more conclusions that can be supported. That said, I think that St. Edburga teaches us that a life of quiet and humble service can be as honouring to Christ as a life of great and adventurous deeds. Writing this, I was reminded of the famous quote from St Mother Teresa: “Not all of us can do great things, but we can do small things with great love”.

Wishing you all a blessed Advent and a Merry Christmas.

Rory Naismith, Early Medieval Britain (Cambridge University Press, 2021), p.329

Naismith, Early Medieval Britain, p.314

There is some uncertainty about this. St. Boniface also addressed letters to a woman named Bugga and her mother, and it is these letters that reference the pilgrimage and meeting in Rome. Most scholars think that Bugga, who was also an abbess of royal birth, is in fact Edburga, but Bugga being an abbreviated version of her name. This is not entirely certain, so it is possible that Bugga is in fact another woman and that St. Edburga did not take a pilgrimage to Rome and met St. Boniface in Wessex.

This letter by St. Boniface to St. Edburga, written c.716, contains a vision of the afterlife experienced by an Anglo-Saxon monk at the Abbey of Much Wenlock, and is considered to be the first native Anglo-Saxon vision of the afterlife. St. Boniface gives St. Hildelith of Barking (not to be confused with St. Hilda of Whitby) as his original source of this vision. Interestingly, Much Wenlock Abbey was another prominent double monastery, and at this time was led by a notable female Abbess, St. Milburga, whose story we will look at in February.

I found this in a fascinating short pamphlet which is freely available online here. It is possible that St. Edburga’s relics were translated to Lyminge because Minster Abbey already had the relics of the more famous St. Mildred, who had a well-established cult, and thus St. Edburga’s relics were in a sense surplus to requirements. Translating them to Lyminge could have been part of an attempt to develop an independent shrine there.

I loved learning about the connection between Saint Edburga and Saint Boniface. Fascinating!

The early medieval period is so interesting, and so many admirable people to learn about :)